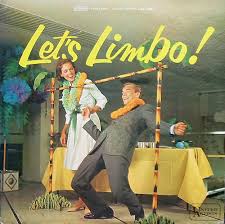

An old friend commented on a chapter from the novel I'm currently publishing to the web, Learning to Limbo. He said: "How do you come up with this stuff? It's amazing!"

"I lived it," I replied. And it's true. Much of Learning to Limbo follows Mark Twain's advice to "write what you know."

Such advice might seem sorta stupid. How can we write about things we don't know, right? On the flip side, there's this quote from P.J. O'Rourke:

“Creative writing teachers should be purged until

every last instructor who has uttered the words 'Write what you know' is

confined to a labor camp. Please, talented scribblers, write what you

don’t. The blind guy with the funny little harp who composed The Iliad,

how much combat do you think he saw?”

(O' Rourke's example isn't the best: Homer was more of a compiler and adorner of campfire stories that had been around for centuries than he was an originator of those stories.)

One of my favorite novelists, Saul Bellow, based much of his fiction on real life experience. With the exception of Henderson The Rain King, (Bellow's hilarious meditation on anthroposophy), Bellow's novels follow the arc of his own life, from the youthful Adventures of Augie March, into middle age with Herzog (Bellow really was cuckolded by his wife and best friend), on to his 60s with Humboldt's Gift (he really did have a friendship with a poet, Delmore Schwartz, whose life closely mirrored the character of Humboldt Von Fleischer). Even Otto Sammler is a mouthpiece for Bellow's philosophy in his later years.

One of my favorite novelists, Saul Bellow, based much of his fiction on real life experience. With the exception of Henderson The Rain King, (Bellow's hilarious meditation on anthroposophy), Bellow's novels follow the arc of his own life, from the youthful Adventures of Augie March, into middle age with Herzog (Bellow really was cuckolded by his wife and best friend), on to his 60s with Humboldt's Gift (he really did have a friendship with a poet, Delmore Schwartz, whose life closely mirrored the character of Humboldt Von Fleischer). Even Otto Sammler is a mouthpiece for Bellow's philosophy in his later years.John Irving fans know that he tends to include much of what he knows – wrestling, New England, Vienna, private schools like Exeter, his experience as a professional creative person (writer, but also actor, organist, children's book author etc.) – in his novels. Sometimes reading an Irving novel is like spending a week at his summer house going through family photo albums, over and over. To some, Irving may be a case of "write what you know" run amok.

I'm not nor ever will be in Bellow's or Irving's league. In fact, it wasn't until I was 45 that I began to conjure real stories, often inspired by events in dreams and blended with my own experience.

In my first published novel, Hack, I put a portion of myself, and my life, into the body of my best friend, the late Ted O' Connell, and turned him into an unemployed landscape painter named Henry Griffin. I do, in fact, paint landscapes, often while listening to Miles Davis's Bitches Brew.

What else did I write about in Hack that I knew, or was actually true in one form or another?

I really did have comforting dreams about my childhood sweetheart, who appeared to me as sort of an angel. I used her physical characteristics for Hadley Scofield, but what I knew of her adult personality didn't give me enough to go on, so I embellished. We really did play with Sherri Lewis puppets in first grade: Lamb Chop and Charlie Horse, and we refer to each other by those names to this day.

Mr. San Anselmo is a real person, though I haven't seen him in years. His real name is Mark. And all Marinites should know that the character of Razor Rick Morgan is a blend of George Lucas and Metallica's Kurt Hammet, or one of those other emperors of Lucas Valley.

I have never driven a Fat Boy or even been on a Harley, but the Hadley Schofield character really did race motorcycles in her youth. We did drop Orange Sunshine at Alpine Dam, several times. And I'm told that a spinet was dumped off the damn into the reservoir in the 70s.

Russell Chatham is a real painter, though I don't know if there's an exhibit at the Oakland Museum that's dedicated to California turn-of-the-century plein aire painters, or if E. Charlton Fortune's work hangs there.

The only access to the cabins on Pinecrest Lake is by boat, or footpath. It is true that women's menstrual odors infuriate bears. Also, there is a golf resort in Tubac, AZ, which I've played several times. It is where the first half of the movie Tin Cup was filmed.

I really did have a bisexual girlfriend, once – a Francophile – though I can't claim to have participated in a "frisky three-way." And there was an art gallery on San Anselmo Ave. next to Ongaro's Plumbing: The Bradford Gallery.

And the rest of it: Karl, Rex Wilcox, Cyril, Herte, Barbara Bassett, etc. is all imaginary, though based in varying degrees on people I know or have seen in the movies. The plot is entirely imagined as well, though I admit to borrowing the disguise idea from the movie, Mrs. Doubtfire (RIP RW).

Unlike Hack, most of the setup plot in Learning to Limbo is autobiographical. I was out of work as a result of a startup going belly up, and we did move from San Anselmo to Indianapolis as described, even though I had a job offer from Sun and could have stayed. We did have a close friend die from ovarian cancer, and she really did refer to herself as The Practical Princess.

We did live in a wonderful four-poster in Wellington Heights, Washington Township, Indianapolis for about a year. The outfit I joined in Indy was subsumed by it's parent, and we really did move to Ridgefield, CT. My son is really a naturalist and teacher of primitive living skills, and I really did fancy myself a songwriter for many years. I built an awesome treehouse in Connecticut, but nobody fell off the deck.

The rest of Learning to Limbo is made up. Basically, I took this cross-country professional odyssey and used it to satirize the corporate experience. I also used it to juxtapose the banality of corporate existence with human experience: family drama, affairs, and other things that matter more than corporate double talk. I haven't read up on how much an author should admit to being real in a work of fiction, but I do know that readers can tell when an author is writing from a place of personal knowledge, even if that knowledge is of something imagined, or not.

The Healing of Howard Brown, and others

The novel I'll publish next, The Healing of Howard Brown, is autobiographical in the sense that it attempts to work through the shock, pain, confusion, grief, and general altercation in the state of affairs following the deaths of one's parents. I experienced all that and more in 2008/2009 when my parent's checked out, along with a fair amount of inelegant behavior in the remaining family. But, like Bellow's attempt to work through being cuckolded by his wife and best friend in Herzog, the setup or situation is just a backdrop. Like a theater set, it provided me with context for the dispositions of the characters, as well the rich soil needed for the seeds of conflict to sprout and flourish. And, while The Healing of Howard Brown draws a great deal of inspiration from my labyrinthine Southern ancestry, the actual "healing" of the protagonist is, I'm sorry to report, purely fictional.

Based on my experience to date, I can say that those stories that draw from my own life could be considered "low hanging fruit." The settings, the imagery, the characters, and to a lesser degree the plots of my first three novels are drawn from experiences that, being mine, are always relatively close at hand. I wouldn't go so far as to say that drawing from my own experiences has made it easier to write, but I would say it gives my imagination access to events, and people, and the associated imagery and emotions, that are immediate and close at hand.

The other current novels in various stages of disrepair – Chasing Byron, Bury Me With My La-Z-Boy, and The Bolinians – are almost pure flights of fancy, though the historical references in each of them are real enough.

Chasing Byron, set in the same locale of eastern Louisiana as Part II of The Healing of Howard Brown, challenges the historical fact that Byron Nelson won 11 consecutive PGA tour events in 1945, a record that still stands. It attempts to be both a portrait of the postwar, Jim Crow South, and a fantasy about The Gods of Golf and their supernatural influence on the protagonist, young Wyatt Johnstone.

Bury Me With My La-Z-Boy was begun during NaNoWriMo, (National Novel Writing Month) and is a combination genre mystery and zombie thriller, also set in eastern Louisiana. The Bolinians, which is in it's infancy, is historical fiction that chronicles the adventures of a traveling band of Russian/Miwok dwarves and their Russian leader (and biological father), former fur trader Dmitri Pavlovich, as they interact with the real people and historical events of Northern California in the19th century.

I don't know if the low hanging fruit novels, where I am "writing what I know" in a relatively strict sense, has made those stories any better or more engaging than the stories that are more removed from my direct experience. Hopefully I'll be around long enough to find out. It's always possible that some other idea will come along – like the "aspirational" story of the old man, given a year to live, and his band cronies touring the USA in a Country Squire caravan. I suppose that there's only so much writing we can do about what we know, since there's only so much we can know. Then again, a new dream is born in my overly noisy noggin almost every night, and if I can just remember to jot a few things down there may be limitless things to know and write about. Until, of course, there isn't.

Read Learning to Limbo,

online and in serial,

right here, right now!

***********